Why are so many intelligent, sharp, knowledgeable, and articulate wound care and regenerative medicine professionals unable to gain customer trust and drive product adoption and usage?

Introduction

Years managing advanced wound care centers and advising investors, device, and services firms in the industry have given me countless opportunities to be on both sides of sales and marketing activities.

Sometimes, I’m on the buying side of wound care: Deciding which dressings, offloading devices, allografts, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), and other consumable and capital medical devices to budget for and purchase, like when I was a director at Healogics in the US. Or when working with international healthcare services firms and investors considering adding a wound care service line to their existing or planned hospitals, clinics, or rehab centers (and if so, how to proceed).

Other times, I’m on the selling side: Assessing and negotiating with medical distributors, facilitating a business war gaming workshop for a new wound care product launch in the US, or training wound care and regenerative medicine sales and marketing professionals on how to drive product adoption and usage from the customer perspective.

In both situations, I frequently asked myself: Why are so many intelligent, sharp, knowledgeable, and articulate wound care and regenerative medicine professionals unable to gain customer trust and drive product adoption and usage? In search of the answers, I compiled my experiences and spoke with colleagues and industry professionals. It turns out that I was not the only one interested in this answer. Demand was so strong that I began to offer a specialized workshop for sales, marketing, product specialist, and leadership teams in the industry. In the training program, we focus on the user and customer perspective, demonstrating actionable methods for improving commercialization effectiveness. Following are ten of the most common and devastating mistakes made and some ways to avoid them:

1. “Showing up and throwing up” (instead of asking questions

I’m not talking about the rep running to the bathroom and vomiting during a product in-service (though I’ve witnessed that, too). “Show up and throw up” is a behavior most sales and clinical education professionals are guilty of at some point–especially when in a new role or right after in-depth product training. Often due to nervousness, or simply being eager to demonstrate their newly acquired knowledge, a sales rep (and often the manager or VP) will arrive for a meeting, blurt out a quick introduction, then launch into a rapid fire barrage of product features and technical specifications, regardless of the audience and their unique pain points.

“Asking nurses and doctors questions rather than lecturing them about your product or what to do, is key,” says Isaac (all names have been changed), clinical nurse manager at a leading outpatient wound clinic in the mid-Atlantic US.

A sales professional fresh out of an intense week of training is likely to want to talk about how their company’s antimicrobial foam line has more silver molecules or absorbency than the competition, or that their tissue-based product has a higher percentage of living cells or a thicker extracellular matrix (ECM). It’s understandable behavior, but it’s ineffective.

Rather, establishing a relationship and learning your audience’s pain points by asking questions yields much greater success. Ron, a mentor and sales executive I used to report to, is currently a Senior VP of Business Development for a leading wound care services firm. He quotes one of his favorite sales analogies: “Questions to the sales professional are like a scalpel to the surgeon. It’s the primary tool for doing your job well.” Asking the right probing questions will both effectively build rapport, as well as help you determine which of your products and their features will solve real problems for your client.

When I deliver a workshop for wound care sales, marketing, product, and leadership professionals, I review the call points and personality types involved in wound care purchasing decisions in detail. Participants leave understanding the most powerful questions that can stimulate a valuable wound care dialog to drive more sales than “show up and throw up.”

2. Not having a basic understanding of a facility’s clinical quality, operational, and other metrics (and which ones your customers are most focused on)

The products you sell probably solve one or more real wound care problems. Adhesion, elasticity, wicking, and fluid retention are all examples of important characteristics of wound care products. But of equal importance, can you competently carry on a discussion with your customers about their key clinical and operational metrics and goals that your products supposedly help them achieve?

Can every wound care product manager, account executive, clinical specialist, and executive in your firm or on your team answer (or know how to find out) the following questions that directly affect your customers’ clinical and operational goals and challenges?:

- What are the most common wound etiologies treated by your customers, and which ones present the greatest challenges (and why)?

- Do you know how to define key clinical metrics such as MDH, outliers, and others (which can vary across management approaches and care sites) that your stakeholders are evaluated on?

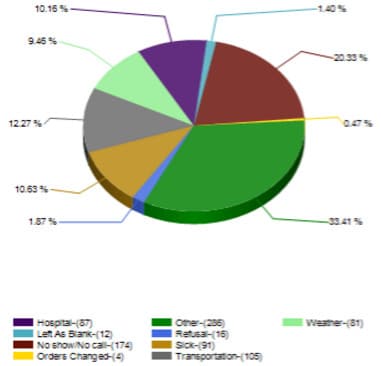

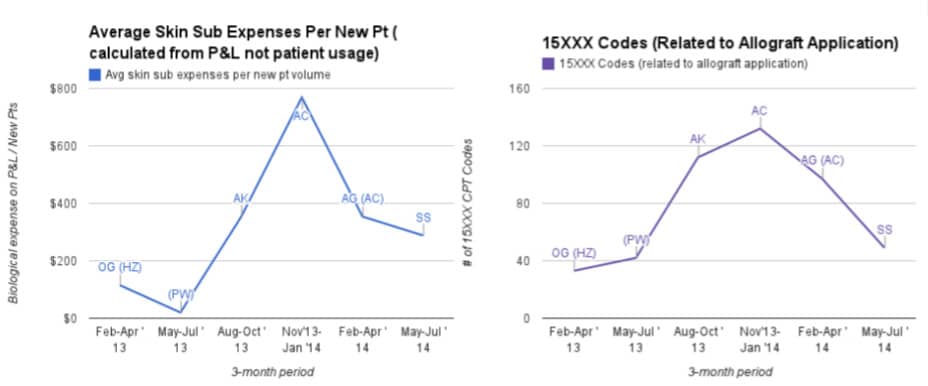

- Do you understand your clients’ key operational metrics, such as staffing and patient ratios, cancellation rates, average supplies per encounter, and clinical flow metrics (see #3 below)?

While an effective NPWT product manager or CTP (allograft) account executive does not need to know all of these points for each customer, a big mistake that many of them make is not attempting to learn more about them when planning or discussing. Strategically, corporate executives can use this knowledge to drive future direction of their R&D efforts and product portfolios. Tactically, field-based professionals can use it as a tool to gain customer trust, and to select which of their product’s features to focus on.

Unfortunately, most employees at all levels of most wound care and regenerative medicine firms are unable to articulate these critical considerations, much less incorporate them into their daily sales, marketing strategy, and clinical education activities.

3. Not understanding and adapting to the clinical flow

When it comes to wound care clinical flow, it’s OK if a wound care salesperson is not a Six Sigma Master Black Belt workflow optimization expert. What is a problem is if they show up and clearly don’t care about the clinical flow or how they impact it.

Every patient care setting has a flow. This is particularly important in the outpatient settings, but is relevant to others, too. Some flows are rigid, some are flexible, and some are a total mess. Regardless, the astute and effective wound care executive has a basic understanding of clinical flow considerations and psychology. S/he leverages it to both improve the relationship they have with their customers as well as to optimize their own schedule by reducing the amount of their week they spend idly waiting.

In well-managed centers, the flow may be more formalized, and will often adapt to patient volumes, the physical layout of the unit, the mannerisms and approaches of the providers scheduled, and the skill mix of clinicians and providers. Various clinical flow methodologies exist, such as “The Case Manager Model,” “Nurse 1, 2, 3,” and several others. Isaac, the clinical nurse manager, even invented “The Hybrid Model,” which combined best practice clinical flow principles and was adopted by several top wound care clinics.

When it comes to wound care clinical flow, it’s OK if a wound care salesperson is not a Six Sigma Master Black Belt workflow optimization expert. What is a problem is if they show up and clearly don’t care about the clinical flow or how they impact it. Some related examples of poor choices include:

- Showing up on a busy day with no appointment (or not offering to reschedule for a less busy day if you show up and the flow is running behind).

- Assuming that just because you spontaneously brought donuts, it is OK to grab the physician for a spontaneous 20 minute sales pitch (the cost of paying the salaries of 10 clinicians and administrators to wait while you schmooze is enough to put a down payment on a Dunkin’ Donuts franchise…).

- Similarly, if the nurse case manager has to pay her child’s preschool a $40 late pickup fee because of that 20 minute delay you caused, she is not going to be your biggest product usage advocate, to say the least.

- Likewise, if that nurse case manager gives her director a letter of resignation because she is unable to consistently pick up her child on time due to the rep throwing off the clinical flow, you’ll likely have even bigger problems.

Clinical flow is not rocket science. But it’s another area where a little bit of preparation and mindfulness can go a long way. The most successful wound care reps not only avoid uncomfortable clinical flow situations–they also find ways to show respect for the flow and even augment it, which when combined with other best practices, subconsciously (though of course not officially) makes them almost part of the wound care team. When training wound care sales reps, managers, and clinical specialists, I generally share clinical flow best practices from my experience as a customer, as well as encourage participants to share their own, which can lead to some very productive discussions and sharing of approaches. Lack of training on wound care clinical flow and how to leverage it into real-world sales and marketing success is another huge mistake made by many sales and marketing professionals working in this space.

4. Demonstrating a lack of knowledge of (or disregard for) wound care/healthcare finances, purchasing, and other operational and administrative considerations

The ambitious wound care sales and marketing professional demonstrates a command of the financial impact of their product or service, yet also confidently asks the right questions to ensure they are discussing the relevant topics with the different different stakeholders involved. This means being able to dive deeper than the words, “It’s reimbursable.”

This is a huge one, and possibly one of the biggest missed opportunities for wound care device and services sales growth. It also manifests itself in many different forms. Ironically, it’s also one of the easiest ones to overcome. In about an hour, I can take a sales rep who may never even balanced their checking account, and empower them to become adept at driving wound care sales by solving financial pain points for their customers.

A wound dressing product manager need not recite all of the reimbursable indications for HBO, nor would I expect a total contact casting (TCC) clinical educator to attend a budget planning meeting with the hospital CFO. However, wound care professionals, from field reps and specialists through the executive leadership level, should have a basic command of the drivers for revenues and expenses specific to each calling point (inpatient, outpatient, SNF, home health, etc.). The ambitious wound care sales and marketing professional demonstrates a command of the financial impact of their product or service, yet also confidently asks the right questions to ensure they are discussing the relevant topics with the different stakeholders. This means being able to dive deeper than the words, “It’s reimbursable.”

Let’s now look at another real-world missed opportunity scenario, this time involving a high-level regenerative medicine executive who failed to apply the proper financial considerations in his sales discussion:

Several years ago, when I worked at Healogics, we would attend quarterly business meetings for leadership throughout the zone to share strategies, challenges, successes, and to be held accountable for any shortcomings.

As was usually the case, a product vendor (in this case the firm was selling a human dermal substitute) sponsored the dinner portion of our meeting–after all, it was a chance for them to present to several dozen directors from across the region all at once. (Unfortunately, vendors spend a ton of money on meals, travel, and presenters for these types of events, but almost always do a poor job of effectively tailoring them to the wound care leadership audience).

The wound center I was leading at the time was a designated mentor site for the zone, had recently won a coveted national award for the second year in a row, and my director colleagues, many of whom came from a clinical or marketing background, often turned to me for guidance on certain business and financial aspects of wound care.

Our product usage of the human dermal substitute being discussed had dropped significantly in recent months. So I was not too surprised when, halfway through the presentation, one of the vendor’s top executives in attendance joined me at my table towards the back of the room. After some small talk, he got right into it:

Him: “How are your patient volumes looking this year?”

Me: “Off the charts. We budgeted for some very strong growth, but it’s even higher than we expected, so we’re looking to hire more part-time nurses to help out on extra busy days.”

Him: “That’s great! So why is your usage of [their product] down so much? I’d assume that with your volumes, your usage would be triple what it is now!”

Me: “Yes, I know we’re using less than before. It’s a good product when used for the right patient and at the right time, but we shifted some of our allograft supply budget this year to staffing so we can ensure we’re properly spending time with and educating patients, which is also very important…”

Him: [Sliding me a brochure] “Look at this study we just put out. We show that on average, every $7,000 worth of applications of our product is going to save $20,000 of total health care costs per patient! Look at how the data…”

The rest of the conversation details are less relevant to this post. But let’s break down what happened in the interaction above:

- He started with two conversational, probing questions (that was good).

- When I brought up our budget and costs, he immediately shifted into a generic “cost argument mode,” and started spouting their new cost study and brochure (which he probably put a lot of effort into creating and probably decided to use even before the conversation began), but was not informed of, nor did he attempt to explore (through probing questions), any of these key financial points:

- Half of the hospital systems represented in that room had recently switched to a new, universal budgeting system (called GBR, global budgeting revenue), that significantly changed hospitals’ financial incentives. Many of them had cut back usage as well, for similar reasons.

- Insurance companies, HMOs, ACOs, and healthcare policy think tanks, all care very much about calculating “total cost of care” but unfortunately, at the time of the conversation (and even today), most clinics and hospital units had (and still have) little if any incentive to be mindful of what happens at other care sites outside of their cost center.

- Under the financial system he was used to, when using his product, a facility would get fully reimbursed for the product cost, but under the new system (which is similar to most European hospital budgeting, and one that many US states and hospitals will likely switch to in the future), using his product would come at the expense of hiring another nurse, using other (perhaps more cost effective) allografts, providing some extra supplies for a charity-care patient to bring home, etc.

Following the meeting, our usage of his product continued to decrease, and we ultimately stopped using it altogether, opting for substitutes instead (our clinical outcomes remained consistent). The executive knew that balancing clinical outcomes with and financial/budgetary considerations was an important driver of my role and decision making process. But in trying so hard to sell me on the supposed surface-level, societal health care economics benefits of his product, he demonstrated a lack of attention to the specific wound care center and financial considerations I was faced with in that role. He also did not address the significant logistical and opportunity costs associated with his product in terms of staff training, ordering, storage temperature, preparation and application, and processing unused product returns, which may have painted a very different financial picture than what was printed on his brochure.

Wound care and regenerative medicine financial literacy is a critical topic for industry professionals to understand in order to sell successfully. It is a topic, perhaps more so than any other, where even a modest amount of education and learning the right questions to ask can be the difference between getting shut out of a facility, or developing it into a top account.

Some more common financial, logistical, and related mistakes that wound care vendors frequently make include:

- Disregard for the administrative burden of setting up charge codes, supply chain processes, etc. and more importantly, what the sales professional can do to alleviate these burdens, thereby eliminating barriers to adoption.

- Not understanding the wound care inpatient, OR, outpatient, SNF, and home health budgets and the effects your product(s) have on them (as well as the product evaluation process for each one).

- Repeating to everyone how their product “is reimbursable” without having any idea what the facility’s supply charge threshold, LCD/NCD, payer mix, vendor policy (see #9 below), or CDM setup process (and a host of other critical factors) are.

- Not understanding the costs and budgetary considerations involving staffing (FTEs, etc.).

- Lack of understanding (or disregard for) the differences in facility vs. professional fees, care settings, and other financial interactions between providers and the sites in which they provide care.

- Ignorance of the structure and financial drivers of a facility managed independently vs. outsourced. For example, if your revenues increase at the expense of the management company’s revenues, you may have a challenge. On the other hand, they may have an internal revenue cycle manager that can independently confirm product reimbursement claims you make to the customer.

- Assuming that it is always better to start by selling to the providers and clinicians, and worry about the administrative and financial obstacles later (in fact, the opposite approach is generally more effective).

Beyond an overview of key financial, administrative, and purchasing considerations specific to the wound care market, one of my goals when training wound care sales and marketing professionals is to equip them with the right questions to ask (and which questions work best with which stakeholder). This ensures that regardless of the customer or latest industry changes, both the field sales force as well as the key support initiatives such as marketing materials and pricing strategy can be effectively prepared and executed.

5. Thinking they still work in pharma (or surgical) sales

Dress to kill, get past the front desk, chat up the doc, get a signature, leave some brochures, schedule a lunch, hope for the scripts, cash the bonus check…wash, rinse, repeat, right?

I’m clearly exaggerating to highlight a point. Indeed, pharma sales are often more complex than that. For instance, a pharma rep needs to be able to manage time, work independently, as well as learn and convey complex indication, contraindication, side effect, and other important clinical info. But in addition to needing those skills, there are crucial scenarios that the wound care sales professional regularly finds himself in that pharma reps seldom, if ever, must navigate. These include navigating diverse clinical settings, offering real-time plan-of-care and treatment support, and selling to/supporting multiple stakeholders simultaneously.

In most wound care settings, non-physician stakeholders drive at least half of the decision making process. In many cases, it’s much more than that.

While there are many transferable and overlapping skills, many successful pharma sales and marketing professionals have a hard time transitioning to wound care and regenerative medicine. When done correctly, they can become top performers. But without the right approach, many formerly successful pharma reps cause big declines in product usage. This has to do with the nuances of advanced wound care.

Firstly, even in the outpatient setting, many wound care encounters involve a combination of diagnostics and procedures, requiring the rep to provide both clinical consultation and product expertise–in real time. How frequently is the average pharma vendor consulted by a provider about a particular patient in real-time (sitting right in front of them)? Likewise, how often is that pharma vendor asked to be present for that patient’s follow-up visits (and do they generally need to explain why a particular treatment is not working for a particular patient)? Wound care vendors, especially those coming from pharma sales, need to learn to fluidly transition between both office and non-office-based clinical settings. While they are not actively treating patients, they must be confident and at ease attending and discussing medical assessments and surgical procedures alike. Without proper new hire training, the pharma-turned-wound-care-professional is often caught off guard by the different dynamics of the wound care environment.

Another mistake that former pharma professionals often make when transitioning to wound care is not taking a holistic approach to the discipline. If marketing an endocrinology or cardiology drug, they were likely focused on just one or two medical specialties and indications. Wound care, on the other hand, is practiced by virtually all types of medical and surgical providers. Moreover, the actual wounds being treated have vastly different causes and less defined standards of care, compared to other specialties and indications.

A third, and perhaps the biggest challenge that the pharmaceutical-turned-wound care vendor needs to deal with is educating and selling to multiple stakeholders simultaneously. In pharma, do the administrators, medical assistants, and other providers in the practice really have a vested interest in which pain killer or beta blocker a provider prescribes to her patients?

In contrast, in the wound care setting, non-provider stakeholders absolutely do care which dressing, NPWT, or allograft are used, since they are involved in purchasing, ordering, applying, and educating the patients–as well as maintaining quality clinical outcomes. If a wound care sales, marketing, or clinical specialist sees the provider as their only customer, without being able to understand and address the needs of the other stakeholders involved (including the patient!), they are unlikely to successfully drive adoption and usage of their products and services.

In most wound care settings, non-physician stakeholders drive at least half of the decision making process. In many cases, it’s much more than that. Failure to properly understand and work with these key individuals is definitely one of the biggest mistakes made by otherwise intelligent, experienced, and successful medical sales professionals. As a result, it is precisely the reps and managers that were highly effective at driving pharma sales that often encounter the most problems when they get to wound care.

To be fair, many successful wound care sales professionals I have worked with did come from a pharma background. These individuals managed to adapt their approach, while maintaining their strengths (such as the ability to distill complex clinical concepts and articulate them effectively). A little bit of inside perspective can go a long way in setting former pharma professionals up for success in wound care, and one that I focus on when working with them.

Don’t treat every outpatient debridement, allograft, or NPWT application as a complex cardiac transplant or pediatric neurosurgery case–especially if it’s a busy day. If you do, you may develop an unfavorable reputation with your stakeholders.

Regarding surgical sales professionals transitioning into wound care, some of the key points are similar to pharma, so I won’t draw it out. Wound care is a complex sub-specialty, and spending time in the OR may be an important activity, depending on the product and situation. Still, wound care sales and marketing is not the same as selling bone fixators, cardiac implants, or surgical robots.

On the one hand, most wound treatments take place in outpatient clinic, inpatient/SNF bedside, or home health care settings (i.e. not the OR). Even the wound care aspect of most OR cases is usually less complex compared to the orthopedic trauma, heart valve repair, or tumor extraction that came immediately before it. The majority of wound care patients will not require an OR procedure to heal (and of the OR procedures rendered, a large amount are vascular interventions, which the wound care vendor usually has nothing to do with).

Still, depending on the product(s) sold, many wound care and regenerative medicine vendors will spend time in the OR. This is totally fine, especially if the surgeon and/or OR staff is less familiar with your product and requests your support. But don’t treat every outpatient debridement, allograft, or NPWT application as a complex cardiac transplant or pediatric neurosurgery case–especially if it’s a busy day. If you do, you may develop an unfavorable reputation with your stakeholders.

Wound care sales has some overlap with pharma and surgical sales, but it’s still quite unique. Many salespeople and marketers transitioning into wound care from those specialties will fail if they are unable to adapt approaches and strengths of each. On the flip side, professionals who are able to apply the right mix of elements they learned in office or OR settings to wound care have the potential to be top performers.

6. Lying about your product (or making up/exaggerating details)

“Many times, reps are not familiar enough with the product they are selling and making mistakes when talking to clinicians who are already familiar with the product. This is a big mistake, but if I feel they are lying or exaggerating to compensate on purpose, I will quickly lose respect for them as a product consultant.”

While one might assume that this mistake is more likely to happen with a new vendor who is still learning about their product, when I informally polled several former colleagues, I found that veteran wound care reps seem to be the main offenders.

It is clear to most people that lying or exaggerating about your product is not OK. Let’s get the most obvious reasons out of the way first: Patient safety, outcomes, and regulatory compliance. While most of your average wound care treatments are not as high-stakes as others (selecting a less-than-ideal dressing is usually not as much of an immediate risk to the patient as, say removing the wrong kidney or administering the wrong drug). Still, many wound patients tend to have other underlying health issues and can significantly decline in between treatments. Even if no patient harm occurs, the legal and regulatory fallout can be in the millions of dollars.

Taking a behind-the-scenes look at some clinician and administrator feedback, we can gain a deeper understanding of why lying (or exaggerating) about your product is a risk that in the long run, tends not to provide a return. Following are some real-world examples illustrating this point:

- According to Brenda, a seasoned inpatient CWOCN, “Recently, a rep told me that [a prominent wound care physician I had worked with in the past] liked his product so much he was switching to it instead of [competing product]. It was totally untrue. Another rep told Dr. Jones he could hook [Company A’s NPWT device] up to run on [Company B’s NPWT dressing]. Who do they think they’re kidding?”

- A sales rep selling an outpatient skin grafting device came to meet with me in a clinic. Concerned about the operational (clinical flow) impacts of performing the procedures in a busy outpatient setting, I asked him what the incremental staffing and time requirements would be when using the product. “Almost nothing,” he replied. “The doc goes in the room, places the graft harvester on the thigh, then leaves while the nurse starts checking vitals and removing the dressing. By the time that’s done, the graft is harvested and the doctor comes back in the room and places it on the wound.” I then challenged him with the notions that: a) The point of checking vital signs is to know if the patient is stable before treatment is rendered, not after; and b) if graft harvesting were to begin before the wound is undressed, then by the time anyone sees the wound (like if it’s infected, worsened, or even healed since the last visit), wouldn’t it be too late to cancel the donor site harvesting? Unfortunately, rather than take back his recommendation, or even ask for a chance to check with his clinical specialist team and get back to me (I think he already knew the answer), he retorted, “Well that’s how [regional university hospital wound center] does it and it works great for them!” Regardless of others’ approaches, I did not think his recommended method would be a big hit with either my clinical team, nor the hospital’s risk management department for that matter. But out of curiosity, I called the regional university hospital in question and spoke to the outpatient wound care clinical manager there to see if it was true that they were actually simultaneously harvesting grafts while taking vitals and removing the wound dressing. “No way!” she replied. “We would never do that. Besides, we trialed the product on two patients and both times we were under-impressed and haven’t used it since!” The product is actually a pretty good one, but patient selection is critical (in theory, almost any patient close to healing could be a candidate for the procedure, but that does not mean every patient should receive the procedure). Beyond the operational considerations involved, if a vendor cannot demonstrate trustworthiness, they will struggle to roll out newer categories of products that require higher amounts of end-user support and education.

- Amanda, a CWOCN and director of both the inpatient and outpatient wound care programs at her hospital, shares her thoughts on transparency in wound care sales: “While they certainly should make every effort to learn their product inside and out, I value honesty. It’s OK to say ‘I’m not sure but I will check and get back with you with an answer.'” Isaac, the clinical nurse manager, agrees: “Many times, reps are not familiar enough with the product they are selling and making mistakes when talking to clinicians who are already familiar with the product. This is a big mistake, but if I feel they are lying or exaggerating to compensate on purpose, I will quickly lose respect for them as a product consultant.”

7. Using the inpatient setting as a back-door to an outpatient sale (or vice versa)

Facilitating communication is one thing. Taking advantage of hectic transitional points and interfaces within the healthcare system to slip in an extra sale is something entirely different.

In advanced wound care, it’s a fact that many patients are medically complex and receive treatment in the OR, inpatient, rehab, outpatient, and home settings, often with several different settings in the same week. Wound care reps and clinical specialists can play a valuable role by helping to ensure that providers at all care sites understand and are comfortable using the products (educating a home health nurse to not “clean out” an allograft or SNF clinicians on proper NPWT application are two great examples of how you can provide value and contribute to good clinical outcomes in these situations). The wound care team will be very appreciative of this type of involvement as well.

However, an all-too-common mistake that vendors make is by attempting to use one care site as a back door to another. You can cause a lot of confusion and other problems when you say, “Dr. Smith had the patient on my brand of NPWT when she was in the SNF, so you need to order a unit of my brand to apply to her wound in the clinic when she follows up next week.” Likewise, the director or purchasing manager of the surgical services unit will probably not appreciate being forced to stop everything else and order a new product for the OR because “Dr. Smith put on my product in the wound care clinic today and he wants to use another one on his OR case tomorrow so you need to buy it.” Facilitating communication is one thing. Taking advantage of hectic transitional points and interfaces within the healthcare system to slip in an extra sale is something entirely different. If you have to stop and ask yourself which category an interaction falls under, it’s likely the latter.

I’ll never forget, shortly after I started my first wound care management position, a sales rep from a well-known, respected regenerative medicine firm tried to sneak in an invoice for a $6000+ product used during a wound clinic visit (it was not reimbursable for outpatient use, and even if it had been, the patient would have been stuck with a $1500 copay despite having a fast-healing, shallow wound). The rep’s explanation when I confronted him about it? “Dr. Jones used it in the OR that morning and wanted to use it in the outpatient clinic, too.”

I subsequently uncovered many interesting details and teaching points in this case, which is a scenario we often discuss and learn from when doing a wound care sales and marketing workshop (especially if the client’s portfolio has biologicals, tissue-based grafts, or other high-cost products). Although I was ultimately able to get the invoice voided, the amount of effort required, and especially the disappointing response of both the rep and his manager (aggressively blaming our clinical staff), negatively impacted the trust and relationship we had with that firm for years.

Despite all the talk about value-based and patient-centric care, the fact remains that most US providers and departments, even within the same hospital, are still very-much siloed in most major healthcare systems and community hospitals. This needs to change, but vendors blurring these lines to sneak in sales is not an effective way to do so. This transitions us into the next major mistake I frequently encounter…

8. Selling to providers across settings (without coordinating with management)

“[W]hen the physician needs to get on the phone with the insurance company or explain to the patient why they did not receive the product (or why it was not covered by their insurance), they are much less likely to continue using the product again in the future–even if the clinical outcome is good. It’s just human nature.”

This one is a bit more nuanced, yet somewhat related to the previous point. Once a vendor has built trust and confidence with the wound care team, it may be totally fine to discuss their products with providers in their private office or another setting. Especially if their designated wound care day(s) is (are) frequently busy, you may be doing a favor (see #3 on clinical flow above) to the patients and staff by providing product education outside of the wound care center. But when done the wrong way, this behavior will actually set back adoption of your product.

Karen, the office manager at a busy hospital-based wound care center describes the fallout from when a rep obtains a list of providers then secretly meets with them in their non-wound care office (or at a restaurant or other setting) to discuss wound care products:

“When a new sales rep gets too excited and starts selling to and buying meals for the docs off-site, the providers may want order the product to be used on the patient without complete documentation or too early in the patient’s treatment [to be approved by insurance]. I then get bombarded by the insurance companies and vendor’s customer service, requesting additional paperwork and signatures. This leads to a lot of wasted time and energy, and the patient may not receive the care they deserve.

“Ironically, when the physician must take a phone call from the insurance company or explain to the patient why they did not receive the product (or why it was not covered by their insurance), they are much less likely to continue using the product again in the future–even if the clinical outcome was good. It’s just human nature.

“Even when the provider education is done off-site, I’d much rather be involved from the beginning. For one, it shows the wound care team that the vendor is collaborating with us, not working against us or in secret. Of equal importance, it allows us in administration to assist by checking that the product is approved for the indication and that the physician documented the required elements before submitting the order. This can save a lot of time and frustration for everyone involved.”

As Karen points out, it’s crucial that off-site product discussions be be done in a coordinated and, transparent manner. If you want to meet with providers outside of the wound care setting, your first conversation should be with the administrator of the unit:

- Ask if they would mind you visiting the provider in his/her private office or inviting them to a product education dinner. Specify which provider(s) you would like to approach (this is a crucial consideration that we get deeper into in live wound care sales and marketing workshops).

- Ask if there are any products that should not be discussed (such as large equipment that there may not be space for), and communicate which specific product(s) you plan to discuss, being respectful of any requests.

- Be sure to familiarize yourself with the facility’s policies and procedures (see #9 below), including their vendor policy, which you should generally follow even when conducting an off-site meeting with the intent of selling products to be used on-site.

- Ideally, even if the provider and staff are met with at separate locations, you will have already educated the facility staff on the relevant considerations such as ordering and application. This way, if the provider wants to use the product immediately, everything will go smoothly.

For this highly sensitive topic, I generally recommend sales professionals use an actual checklist, such as the one provided in our wound care sales and marketing workshop. When executed correctly, this tactic will build trust between you and the center administration, and save you time and energy by focusing on products that you have a chance of selling (for instance, you may have a great non-adherent contact layer, but that facility may have recently signed a 3-year contract with another brand for that product category).

A big mistake that many wound care reps make is in thinking they’re being smooth and innovative by calling on the providers behind the backs of the wound care leadership team. Is it illegal? No. Is it unethical? Not really. Can it negatively impact professional trust and patient care? Absolutely. Following are some actual issues that arose because wound care reps sold to providers without consulting with me or my administrative team in advance:

- Patient arrives for outpatient appointment expecting a product or procedure that we were neither aware of, nor setup to order in the purchasing system.

- Patient told will receive a therapy that neither provider nor clinical staff have been trained on.

- Provider misinformed of (or misunderstood) contraindications for a product; clinician has to diplomatically bring him out of the patient’s room to and show documentation (both embarrassing and harmful to the patient’s confidence in the physician and treatment).

- Rep recently transferred to region from another part of the country that had vastly different reimbursement criteria for the same product she had sold elsewhere; Physician told patient in her private office, “Come to the wound center next week and we will apply the product,” resulting in poor patient satisfaction when it was not applied (and had it been applied, the patient would have received a large, unexpected bill for it).

When done properly, most administrators have no problems, and may even appreciate, a vendor educating a provider outside of the wound care facility. But doing so in a non-transparent and uncoordinated manner can lead to both short and long term problems that generally outweigh the extra few minutes of potential provider face-time.

9. Not knowing/respecting the facility’s policies and procedures

Meeting sales quotas can be a lot of pressure. But not learning or respecting the facility’s procedures is never going to help you hit your numbers in the long term. Sure, there may be some obscure rules that even some of the staff may have no clue about–I’m not referring to these. On the other hand, there are several crucial considerations that need to be on your radar.

Katie, a Senior Director of Clinical Operations for a large wound care services firm (who started her wound care career as a home health nurse before transitioning to a clinical manager), shares two of the ways that sales reps and clinical specialists can quickly lose their welcome: “Not knowing, understanding, or observing HIPPA regulations and impersonating a clinician [by] wearing scrubs and wandering the clinic.”

While it can be tricky in a crowded and busy facility to totally filter out every passing bit of HIPPA info (especially if some rooms have curtains, not walls), vendors in these environments need to be especially aware of and sympathetic to the consequences that providers, facilities, and their business associates face for breaches.

Vendors wearing scrubs can be another grey area. Some facilities and outsourced wound management firms in the US have specific policies against vendors wearing them, because it can give the impression to the staff (and especially to the patient) that a vendor is part of the clinical team, when in fact they usually have no such designation (and should not lay hands on the patient). On the other hand, for a sales rep providing product education and support in the OR setting, wearing scrubs is required. It can also facilitate hands-on demonstrations such as compression or TCC applications during a clinical training in-service. Furthermore, many sales reps, clinical specialists, and executives are registered nurses or have other relevant clinical certifications. I even know some that still hold part-time positions where they provide direct patient care. Still, at a minimum, they need to know and respect the policy of the facility and management company (if there is one).

According to wound care program director and CWOCN Amanda, “I once had a rep suggest to myself and my provider that they ‘help us’ identify a patient [to use their product on]. This obviously was seen as ‘poking the bear.’ While the sales rep may potentially have more knowledge on their product, it would be crazy to suggest they were more competent in identifying a patient than the clinic staff.”

Amanda shares some additional behaviors that can turn an otherwise professional wound care industry representative into persona non grata in her clinic: “While our sales reps often also become ‘our friends,’ they should not be near phones, back offices, computer, or nursing/provider conversations unless formally invited there for a specific product-related reason…[nor should they] act like they need to shadow the clinic to get some type of ‘mandatory rep training.’ Besides this being at odds with every hospital and clinic policy I’ve seen, it’s just not truthful” [Author’s note: This claim also always bothered my teams and me–and sometimes led to me calling the district sales director/VP to have a discussion about professional ethics].

Discussing product reimbursement with staff is another potential pitfall, and may violate the facility’s vendor policy in addition to causing other fallout.

For the vendor, the best case scenario of a policy transgression is that perhaps one or two of the center team members will happen to notice and quietly resent it. A less common, yet painful outcome is being banned from the clinic, facility, or in extreme cases, your entire company’s sales force may be suspended from sales calls for several weeks or months while your firm’s compliance team scrambles to get back on the good side of the management company or healthcare system’s compliance, risk, and legal departments. Although rare, these situations are not pretty, and can result in hundreds of thousands–or millions of dollars in costs, lost goodwill, and of course missed sales and loss of market share.

Many well-managed wound centers and SNFs will provide vendors with a short document highlighting the facility’s vendor policy. Medical device, pharma, and services firms calling on the wound care industry should provide resources to ensure their sales teams don’t end up on the wrong side of these policies. While it’s impossible to maintain up-to-date records of every vendor policy at every healthcare facility, when we run a wound care sales and marketing workshop, we always cover the most common topics and how to avoid any embarrassing and costly episodes.

10. Giving up on accounts and not trying again later (and taking active accounts for granted, thus failing to support them)

Wound care sales and marketing are not easy. The patients are often complex, the products require hands-on familiarity, reimbursement can be challenging, and there are many aspects out of your control. One of the most common, and unfortunate, mistakes I see is the wound care rep who comes by once or twice with no traction. Maybe the clinic was too busy or understaffed those days, maybe the inpatient CWOCN was on vacation, maybe the leadership was preparing for an inspection, or maybe you didn’t ask the right questions.

Wound care is one of the fastest growing medical sub-specialties. Sometimes, a strategy or tactic that did not work last year will work again this year. One approach that can be helpful, is the next time your boss or a corporate executive is in town, take him or her to the client where you’re having difficulty with (not just to your best accounts). Perhaps your approach and products are great, but there’s another rep who has a great relationship with that client (for example, he was there with them since the facility opened), but eventually they get promoted and move away from that region (it happens often!). Maybe you made one (or more) of the other 9 mistakes discussed above during your first visit, and things need some time to settle down a bit (or the staff and physicians have changed since then). You can take an extended break, but don’t give up permanently.

I can recall countless times where a sales representative or regional manager tried once or twice to get traction in an account I was involved with, without success. In many cases, the timing was just not right (either the specific days(s) or the general period, such as immediately before or after key stakeholders were leaving on business or personal travel). Months or even years went by without hearing from that individual.

Eventually, due to restructuring, redistricting, transfer, resignation, or another reason, we would get a new sales representative/manager. In many cases, our (the customer’s) situation had changed slightly, or the vendor had a new offering, or perhaps the new rep’s approach was simply more effective. On many occasions, we ended up purchasing the products, even becoming a top account for that rep. Likewise, when reps whose products we frequently used chose to not check in or provide support for extended periods, they often became replaced by a competitor who was more adept at providing follow-up. By the time the prior rep would see their numbers plummet and make a point to come by, it was too late (Rule of thumb: If you come by an active account and there are two or more employees that you have never met, you’re likely not providing enough support and at risk of a competitor capturing that business).

The point is, whether you’re a new rep or distributor, a seasoned product or clinical specialist, or a veteran sales and marketing executive, don’t give up in the quickly-evolving wound care industry. Becoming complacent and not showing up at your active accounts, or ceasing attempts to break into new ones, are common yet costly mistakes made by wound care and regenerative medicine sales professionals across care settings, geographies, and product types.

Conclusion

When I work with wound care and regenerative medicine companies to give their sales, marketing, clinical specialist, and leadership teams a comparative advantage, we typically review everything from the wound care product decision making process, to finances, to strategies for approaching an introductory meeting vs. a product in-service vs. an educational dinner. But we also make sure to discuss common yet costly mistakes like these, which can devastate product adoption and usage (usually without the vendor even knowing).

Might your wound care or regenerative medicine firm benefit from our customized course addressing these and other key issues affecting your sales growth? New hire on-boarding, sales meetings, clinical and product training, as well as strategic and leadership/executive team meetings find particular value in our actionable, refreshing course.

Contact me to review your wound care growth needs and how we can provide your team with a competitive edge. Connect with me to receive updates.

What wound care/regenerative medicine sales and marketing mistakes have you come across? How often do you think they result in missed opportunities for adoption and sales? Please comment below!

Brilliantly stated!

I have had several experiences as a patient with a wound care center in Ohio. To be brief, I believe they are routinely abusing debridement as a means of boosting profits. I first ran into this as an outpatient with a small 10mm weeping wound. W/o any discussion I was painfully debrided. Only when I got the bill for over $2000 (operating room, recovery room, etc.) did I become aware that I had ‘surgery’. Later I cured the same type wound with ‘Dermaginate’ on my own w/o w/o debridement, saving $2500. I was told it IS considered surgery. If the case, why isn’t the patient informed or asked for consent? Why don’t they need pre-approval from insurance? Basically all the usual rules that apply with surgery? Since then my wife an I visited wound care 6 times each, and EVERY time they were preparing us for debridement BEFORE even examining us. Again, she didn’t realize what was happening until she got the bill. But this time insurance paid nothing. Forewarned, when I returned for edema skin ulcers, the nurse was already to apply Lidocaine for debridement. Every time, w/o explanation, they attempted to go ahead with such until I told them to STOP. NO CUTTING!. This was so routine, they don’t even think about it. I insisted on alginate as a treatment, which worked again. So, there are alternatives they not only don’t discuss, but don’t even consider. My wife’s toe wounds had scabbed over, but they debrided anyway, later claiming there could be infection underneath. But my GP prescribed me a generic antibiotic that targets skin issues. Another alternative w/o surgery. Although the procedure is an accepted alternative, the way it is so routinely practiced here, to me is borderline unethical and casts doubt in patients’ minds if there to be cured or skewered. What happened to informed consent???? Am I unreasonable?